Interview with Franck Leibovici (by Grégory Castéra)

Forms of life and ecosystem of an artwork. Interview with Franck Leibovici by Grégory Castéra (translated by David Pickering)

Monday 10 a.m., in the kitchen of an apartment

Grégory Castéra Good morning, Franck.

franck leibovici good morning.

GC We’ve never seen each other this early.

FL yes, it’s hard.

GC Do you have a lot of other appointments today?

FL i was born tired.

GC Let’s get started. Would you like some tea?

FL no, just water.

GC Are there any clarifications you’d like to make regarding the notion of forms of life based on early responses to the survey?

FL perhaps there is one point that has to be clarified. the survey is not in anyway based on a request for autobiographical confession or a causal explanation – it isn’t, on the one hand, “i had a child and it changed my life,” or, on the other, “the art market is terrible, the economy dictates everything.” these are two types of answers that miss the subject. because a “form of life” is linked to practices and implies interactions, it is necessarily always already public and collective. that is what we’re asking artists to describe. we aren’t looking for an explanatory model (the grand reasons) – if we did we would fall into fairly weak sociologisms. we simply want to explore an otherwise obscure terrain of which we know neither the composition, nor modalities of production, nor modes of functioning. basically we are asking artists to take us on a walk through their ecosystem.

GC If I understand you correctly, you’re asking them to describe an ecosystem rather than give practical explanations about a practice. Instead of the example you give, “I had a child and it changed my life,” you want them to describe how the relationship with the child constitutes their practice – I’m thinking for example of the relationship to learning or putting aside time to take the child places.

FL you could put it that way. in your example we’re trying to see how the practice includes the child, rather than making the child the theme.

GC Does forms of life include ways of producing a work collectively? I’m thinking of modes of production in performance, but it seems to me that this remark could apply to all artistic practices. Actually, defending the idea that an artistic practice is necessarily a collective endeavor is one of the pillars of our project as directors of Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers.

FL you’re right. in the last few years performance art may have made these particular modalities more explicit and more prominent (when you paint a canvas, these elements are more often implied or implicit). however they definitely apply to all artistic practices.

GC Yes. Beyond the process of “manufacturing” a work and the people directly involved, the ecosystem you’re referring to might materialize through the knowledge and practices utilized in that process. I am thinking of reformulating a project each time i present it and of certain attitudes that develop more or less tacitly and contribute to creating “a working atmosphere” – speaking and listening to others speak (which implies handing out roles within a collective) and day-to-day changes in the way artistic research is “nurtured.”

FL absolutely, but how do we represent an “atmosphere”? how do we make it explicit, beyond writing the chemical formula of the gases it contains? i remember, a few years ago, google created a little application called zeitgeist. i guess i would say it tried to answer the question: “what about you? if you had to represent the spirit of the times, how would you go about it?” google tried its best to answer that question using its own tools.

but our survey isn’t only intended to represent a rigid state, frozen in time. it involves a whole range of questions that try to take stock of a process: what is required to keep an ecosystem going? what kind of care does one have to give it? the french talk about maintenance but the english term “sustainability” is better. how to make it sustainable? how to make it viable? we could also formulate things in terms of exercises. which exercises do your practices require? exercise, whether spiritual or physical, possesses that everyday quality that is integral to an ecosystem. another possible formulation might be: what type of discipline do your practices imply? if we take the term discipline in the widest sense (an athlete has a certain asceticism, meaning a diet, a schedule, etc. and so does an artist).

GC Do you want some more tea?

FL water, actually.

Tuesday, 3 p.m., a telephone conversation.

GC Hello, Franck.

FL hello.

GC Do you have a minute to continue yesterday’s discussion?

FL uh-huh.

GC Yesterday we talked mainly about the production of works. Your project involves forming a community of practitioners who will discuss their forms of life and produce documents describing these forms of life. What will the project entail from the public’s point of view?

FL i’d say the public is at the very core of the project, even if the road is long. beyond appealing to artists to mobilize these capacities for inventing forms of representation, we’d like to succeed in modifying ways of “seeing” an artwork. on the most basic level, we would like this project to modify and heighten the viewer’s “sensitivity” to an artwork (the predisposition to be sensitive to it) so that standing before an artwork triggers routines other than the standard operation of reduction of the object. instead, we want the viewer to ask the question, what form of life is behind or around the work? what bigger picture is this object a part of? that way we can form another idea of what an artwork is (create forms of life) – and that other way of “seeing” will also constitute a discriminating criteria. formally similar works might then be completely reevaluated and radically distinguished.

GC Though looking at artworks as ecosystems allows us to attribute less importance to their form, doesn’t the approach disqualify any Universalist dimension of the work, making it necessarily dependent on its context?

FL it’s not that less importance is given to the work’s form, on the contrary. what the project points out is that the form of the work is not what we think! the form of the work cannot be reduced to just the exhibited object – it is the form of the entire ecosystem. if such a large misunderstanding exists it is because we don’t know how to represent this ecosystem. it remains baffling; we don’t know what the form of such an ecosystem would look like. in plain language, if the definition of an artwork includes the practices it incorporates, then we don’t know what an artwork looks like and that’s a problem for me because i don’t know what i am supposed to be looking at, or how far i am supposed to be looking. this question of universality versus context is moot. the point isn’t to prove that context is everything; the point is to follow practices, mediations and narratives. when i am told that a work of art transcends all that, transcends its ecosystem –all right, but where does it go from there? i would just like to know what an ecosystem looks like because this form of knowledge allows me a more discriminating relationship to works than knowing that they transcend one another.

actually, if we look closely we can also brush up against the definition of what an object is. it is no longer a fixed essence, existing for all eternity, but is defined by its uses. it becomes a sort of continuum across which a cursor can be moved. the object re-attains a certain ontological plasticity. in reality this is nothing new, it has always been the case, but let’s just say that modernism has a tendency to make these mediations on what comprises an ecosystem invisible. the aim of this project is to make them explicit, make them more opaque, and then, more palpable.

GC Thank you. What would you say to writing down this exchange in the form of a dialogue? A sort of reconstitution of the form of life we’ve established in our work together?

FL it’s true that the project has developed in a large part through conversations with artists who have received the letter. it actually began with conversations paresseuses with christine macel… see, you’ve stopped counting your cups of tea. it’s a work method that is both rich and flexible. its resource is the time we spend together. oh, i’m almost out of batteries and my telephone is turning into a microwave oven for my ear!

Interview published in Le Journal des Laboratoires May-August 2011

Interview with Franck Leibovici (continuation)¹ by Grégory Castéra (translated by David Pickering)

1.

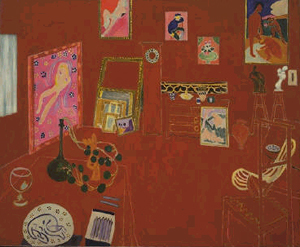

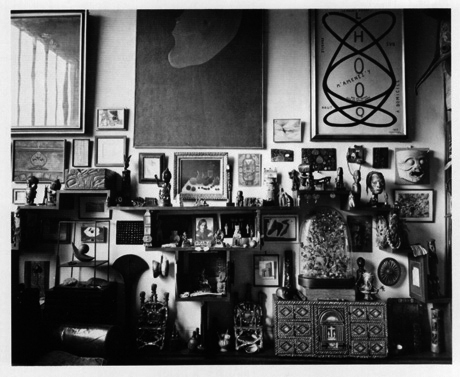

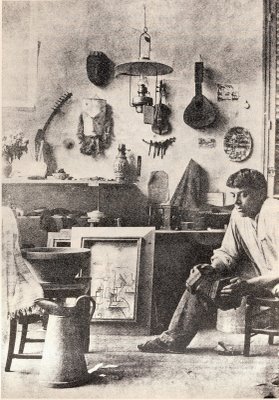

franck leibovici …in each of these images you’ve laid out in front of us the atelier is shown differently: matisse depicts some objects on a table and others hanging on the wall; braque does the same but adds a figure engaged in some sort of leisurely, secondary, but no doubt complementary activity; bazille, on the other hand, populates his work space with individuals—probably friends of his—going about various tasks (one plays the piano, others discuss serious business, and so on). the issue of the atelier you are bringing up here is interesting but i sense that it doesn’t completely coincide with “forms of life,” for the atelier immediately suggests the production cell, while the notion of ecosystem strives to break free of its production-exhibition-contemplation sequence. on the other hand, it could be amusing to consider which forms of life these images of workshops imply. the question of whether one turns it into a solitary space or, on the contrary, a social one, is telling. empty it out or fill it with people: two forms of work that sometimes overlap.

Grégory Castéra I showed you these images because it seems to me that the theme of the artist’s atelier, because of the wide range of documents and works it includes, is what is popularly expected from a behind-the-scenes production of an artwork and the representation of an artist’s life. It was in high school that I discovered this photo of André Breton. It conjured up a certain idea of the “cultured man.” I interpreted the collection in the background as an allegory of the knowledge accumulated over a lifetime—a mix of cultures, noble materials and refined taste. Like a library, the collection is an archetypal representation of a form of life², as much in its composition and organization as its uses. But for your project it strikes me as more interesting to know how the collection was amassed. Though I knew strictly nothing about Breton, I imagined him as a decisive man who asserted his opinions in public, a misogynistic charmer with a personal fortune sufficient to allow him to travel, buy artworks, live in a nice apartment and have to answer to almost no one…

fl …when the truth is his rue fontaine apartment was quite modest, and many of the objects were acquired at drouot (a Parisian auction house, Tr.), and had very little monetary value at the time.

Henri Matisse, L'Atelier rouge, 1911.

Frédéric Bazille, Edouard Manet, L'Atelier de Bazille, 1870.

Sabine Weiss, L'Atelier d'André Breton, 1960

Atelier de Georges Braques

2.

GC Among the answers we receive, some artists propose works, others documents. How do you take into account the status of propositions in your survey?

fl it was not I but certain artists who created this artwork / document division. once again, what is being asked for is an invention of forms of representation. in that respect, the survey deals with a poetic question, in the etymological sense of “the creation of a form” (poiein). in order to be relevant to this survey a response must invent a form. in my opinion, its status therefore comes prior to the artwork / document distinction.

GC Yesterday, we met with ______. He said that his contribution to the survey would be textual. Furthermore, he distinguishes his works (which are mainly installations and sound pieces) from the documents he publishes in book form. You told him that, to represent a form of life, the techniques the artist masters may prove more appropriate than texts. Though the text is conventionally recognized as the principal technology of discursivity, you assert that “a painting can be a theoretical proposition.” It might be useful to explain the controversy to which this assertion refers.

fl yes, texts or conversations are tools that are traditionally mobilized to contextualize, place, or categorize an artwork. at a gallery opening, it is not uncommon to see an artist give a guided tour of the exhibit or pen a text that functions like a statement of purpose. but i am more interested in an artist who uses the tools of his trade, the same ones he uses for his practice, to try his hand at the representational invention being asked for. i am not looking for a causal explanation of artworks, nor am i looking for commentaries on artistic practices. it would have been altogether possible to ask an art sociologist to study the practices of a group of artists, and to deliver an analysis. but this is not what i’m looking for. it is not only important for me to ask the studied group’s indigenous members to represent their respective cosmogonies—i am also trying to avoid meta-language as much as possible in this representational work. that is why the request is so difficult: the artists are being asked to use the tools that constitute their practice, to produce representations of their ecosystem. in no way are we asking them to return a commentary on their practices that is meta- (“documentation” or the para-).

GC Still, it seems to me that producing the representation of an ecosystem could come close to a meta-language. In other words, producing a language that consists of speaking about the language itself.

fl not at all. meta- implies a distance, and a difference in altitude (we place ourselves just above). here, the re-description happens from within. the vocabulary used is none other that that ordinarily utilized by the artist each day. when we are in the middle of things, we can survey the territory, and describe what we see, but we will never try to exteriorize, or step outside ourselves. that would be like trying to grab oneself by ones own hair.

the project asks for an effort at inventing representations. there is always the fear that answering with a text or a conversation might only meet the requirements of part of the survey, the content part, while leaving out the question of form. unless of course the artist thinks of the conversation or the text as one of his or her practices, as is the case with david antin³ for example. this is the opposite of a survey in which you give answers in the form of statements. unfortunately statements are no help at all because they function in something of ameta- mode. in terms of an utterance, the statement expresses the subjectivity of an “i”. “i think that…” (generally followed by an expression of indignation). instead, the notion of “form of life” tries to shed a rather simplistic “i” and to construct a somewhat more articulate collective utterance. we need maps, not statements.

GC So a painting can be a theoretical proposition because it can be more useful than a text for charting a practice.

fl a painting or anything else. yes, a painting can function as a theoretical proposition. we must distinguish the mode of written expression (theoretical, creative, informative) from the format used (scholarly article, handbook, vacation book). even though the two are habitually lumped together (it is mainly in scholarly articles that we are used to finding theoretical writing), we benefit from differentiating them because it gives us greater freedom of action. a mode of writing can lend itself to different mediums, different formats, different platforms, just as a format (medium, platform) can accommodate different writing modes. jean-luc godard puts it very nicely in his early texts when he says that, at the cahiers du cinema, he made movies, but with paper and a pen, and that later he continued to theorize, but with a camera.

GC In other words, if I went back to your earlier remarks about meta-language, and painting as a theoretical proposition, there would be a misunderstanding about what we consider theory.

fl poets or artists often make much of their refusal to “theorize on” their practice. obviously if we were asking them to lay it on thick, or produce a wordy commentary intended to add value to a work, that would be understandable. but maybe there is a misunderstanding about what theory is, maybe it’s a preposition problem—theory isn’t “about” but “in” or “within,” it is concomitant with practice. they are two sides of the same coin. moreover, quite often, these same artists elaborate their practices based on a very clear “theoretical position”: they know exactly what they are doing, they refuse a certain number of things, and develop a clear direction. but that initial refusal disappears when they stop talking about, and begin surveying, a territory. in fact, we might almost say that their practice fashions their theoretical position. in emmanuel hocquard’s title, “theory of tables”⁴, we get a clear sense that the theory is not of a meta- order: “theoria” means contemplation. why “tables”? a table is a platform, it is what allows us to set things down: without a base, without a platform, objects would fall to the ground and crumble. a table is definitively what allows us to see things, to put several of different natures side-by-side. thus the table becomes a visualization technique. a “theory of tables,” is what we do when we ask ourselves how to display objects, how to make things visible which so far don’t have a frame, how to stabilize them. tables offer another scale with which to define other frames of perception. theory only has very little to do with the meta, it deals above all else with questions of scale.

3.

GC A large part of the work with the team at Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers and the artists that participate in the survey consists of explicating the lexicon we use—“forms of life,” “ecology of a practice,” etc. The application of these terms to a field in which they don’t belong falls under the definition of what Nelson Goodman called “metaphor.”⁵ For Goodman, a metaphor is linked to a set of uses, and can therefore only be designated for a given period. In that sense, the job of explicating, which we are laboring at in the ordinary stories, seems to me to correspond to a “de-metaphorization.”

fl i agree completely. we should look at this project as an attempt to literalize the expressions “forms of life” and “ecosystem”: these terms are not yet “implanted” in current usage, but they could prove very useful for changing some things, or escaping certain aporias. the job of re-description asked of the artists, which consists of giving an account of their daily routine, literalizes what could have formerly been considered as metaphorical.

in that respect, de-metaphorizing and literalizing (in other words, describing) means proposing a new lexicon and, as a direct result, if this new lexicon is used, our habits of vision or action (our beliefs) are altered. suddenly, the objects change scale and format, the reference points are no longer the same—it is no longer only the exhibited artifact that is grasped, but a much larger whole that is given a new name. it’s something like what we were saying in our last discussion: what is ultimately aimed for is the modification of frames of perception of what we call an artwork. and so it becomes impossible to distinguish the political dimension of the project from questions of the ontology of art.

GC In a few words, this modification of frames of perception brings out the types of collectives an art practice might engender—in terms of composition, temporality, dynamics of exchange, renewing membership, and so on. The artworks do as much to form the collective, as the collective does to form them. Is the model that articulates the functions of production/creation and reception/interpretation still operating in the context of forms of life? And how should the idea of artistic discipline be addressed through forms of life?

fl you suggest a very nice formulation there: “this modification of frames of perception brings out the types of collectives an artistic practice engenders.” let’s say that the creation/interpretation model is forking out. the moment when you start linking artworks to the collectives they engender, it becomes difficult to distinguish an audience from a producer, for the participants of a collective are willing partners in the project—whether directly or indirectly—and are, at the same time actors and receivers. they form the project’s “audience.” whoever is able to see the types of collectives an artistic practice engenders, thereby gaining a sort of gestaltist ⁶ ability, will continue to interpret the artworks, but his interpretation will no longer be based on the same groupings.

GC And what of the disciplines?

fl they are one of the producer-impetuses of the “forms of life,” for they are linked to this question of practice, of training and asceticism. actually it is amusing to note that in English when we “practice” doing something, we are also training ourselves to do it. this is true in sports, art, religion and politics.

4.

GC Asking artists to produce visualizations that represent forms of life implies that they chose what they want to emphasize, thus closing off a set of parameters that might be considered as the minimum conditions for contextualization. For example (I am voluntarily exaggerating the criteria): birth place, work space(s), religion and religious culture, political sensitivity, gender, sex, sexuality, income, the portion of this revenue allocated toward consumption, travel, or reinvested in work (very important for certain artists whose practice is linked to new technologies for example), basic and higher education, peers who have had an influence, relationship to the media and to culture in general, other practices (hobbies, day jobs), and so on. In short: what are the criteria for a valid response?

fl yes, it’s true. the survey doesn’t resemble patrick sabatier’s jeu de la verité (TV show in which stars tell all, Tr.). we aren’t trying to get a scoop, or to violate anyone’s privacy. artists will emphasize whatever aspects they deem fit. this requires a great deal of honesty on the part of the artist, for someone who gets by with a smart quip will be of no help at all. on the other hand, accepting indigenous representations also means not evaluating the responses based on outside criteria, or trying to list all of the criteria that might play a role in order to systematically apply them to each case. it is the group in question that decides what tests to put into place to evaluate whether or not an answer is worthwhile, not a set of criteria drawn up beforehand by a ministry or university that tries to judge the relevancy or efficiency of answers. we must therefore wait to see if they help change things or opinions, or whether they just renew the status quo.

trusting artists in their choice of what should be emphasized also means leaving behind a critical posture that would seek to discover thetrue mechanisms hidden underneath the art world, and which preside over its real functioning, in order to better denounce them. i was going to say: if they are honest, artists know what they’re doing when they answer in a given way. but in the end I’ll say this: if they are attentive enough, they will succeed in describing what they do with precision (instead of saying what they think they do). before completing this type of exercise, we don’t know exactly what we do, not because we act unconsciously, but because we automate our routines and, as a result, we make them invisible. in other instances, we frame certain gestures as preliminary to others, when they should be described for themselves.⁷

5.

GC Now that most of the responses to the survey have come in, how will you go about analyzing the data?

fl last week we began to “peel back” the first responses. directors of les laboratoires d’aubervilliers were present, alice chauchat, nataša petrešin-bachelez and you, as well as virginie bobin, who coordinates the projects, claire harsany who is office manager, and anne millet who is communications director. we looked at responses one after another. when one of us knew a little more than the others about the artist in question, he or she tried to contextualize the response. we read these contributions in light of what the conversations added, because, of course, an image doesn’t speak for itself. it was a very enriching, though quite ordinary reading or viewing experience: seeing how a group enters into a decoding enterprise.

this is the job we have been tackling throughout july and august. we’ll see what public outcome is the most pertinent.

GC Though we were able to contextualize some artists’ propositions, we were far from experts on a good many of them. Is this lack of information a problem for certain responses? Can the inaccuracy of our knowledge be of use to you or is it better to meet specialists?

fl that’s a difficult yet central question for this project because it poses the problem of expertise. on the one hand, an image can’t speak for itself. so, indeed, the better we contextualize it, the better we will understand its functioning in the environment for which it was intended. in this sense, the problem of the status of responses, the way we grasp them, is the same as when we are standing in front of an artwork.

at the same time, these responses are meant to allow a different mode of comprehension of the artist’s work, a change of scale. they must therefore allow the works of the artist in question to function differently. which means that we have two possible uses for the responses we are in the process of receiving: either we attach them to a body of pre-existing works and we see how they modify the perception of the whole, or we try to make them function on their own. the first use aims to modify the questions we ask ourselves about an exhibited work or add new ones (what form of life can a given work produce or what form of life is engendered by a given practice). the second use deals specifically with the question of the invention of forms of representation of something we don’t yet know how to represent. in the first case, we’ll be attentive to what is said, and it is during this process of interpretation that we can ask the question of expertise. in the second case, we’ll focus our attention on the plastic character of the response.

obviously, the two uses are not totally dissociable, they feed into one another. but there is always this utopian vision of the tool, which consists of thinking that, for the second case, the invented form might circulate and be applied to other works. we fluctuate between two conceptions of the response: on the one hand, the autonomy and self-sufficiency of its plasticity predicated on the hope that, if it succeeds, it might become almost an “intellectual technology”⁸, a format of description for a new scale; on the other hand, a response-prosthesis, which, when added in a particular way to a specific body, produces a new whole, a new definition of the artwork. in the first case, we dream of a public circulation of tools, in the other, the extension of what we call “artwork” is always achieved through the ad hoc and cannot truly be generalized.

if i wanted to be hard on myself, I would almost say that we find the same traditional tension between singularity and universality here as in the modernist artwork, albeit in very different terms and through very different means.

Interview published in Le Journal des Laboratoires, Sept-Dec. 2011